How it is that Illinois, a jurisdiction not typically associated with a strong commitment to free-market principles, came to be the first state in the nation to allow its insurance rates to be regulated entirely by open competition is something of an accident of history.

In 1970, in a continuation of a trend that many states had followed in the 1960s, the Illinois General Assembly moved to replace the state’s existing “prior approval” system for regulation of property-casualty rates—originally adopted in 1947 in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in United States v. South-Eastern Underwriters, which found that insurance did, in fact, constitute interstate commerce—with a “file-and-use” system.

Under the new system, insurers could begin using rates they filed with the regulator even before receiving explicit approval or disapproval. The only catch was that industry agreements to adhere to rates set by a rating bureau—exactly the sort of collusion at issue in South-Eastern Underwriters—were completely prohibited.

A year later, in August 1971, the law was scheduled to sunset and the legislature neglected to extend it. The result, whether intentional or not, is that Illinois became the only state in the nation with no insurance rating law at all. And it remained such (with some minor exceptions) for the proceeding 52 years.

Until now.

Under HB 2203, up for a hearing today before the Illinois House Insurance Committee, every insurer seeking to offer private passenger motor-vehicle liability insurance in the state must file a complete rate application with the Department of Insurance, which once again would be empowered to approve or disapprove rates on a prior-approval basis. The bill also would prohibit insurers from setting rates based on any “nondriving” factors, including credit history, occupation, education, and gender.

The measure also creates a new system for public intervenors in the ratemaking process, stipulating that “any person may initiate or intervene in any proceeding permitted or established under the provisions and challenge any action of the Director under the provisions.”

In a nutshell, the law would transform Illinois from the most open and competitive insurance market in the country to one clearly modeled after the most restrictive: the inflexible and state-directed system created by California’s Proposition 103.

The question, of course, is why would the state do this? It’s true that insurance rates are rising in Illinois, but they’re also rising everywhere else. Insurify estimates that the average cost of auto insurance rose by 9% to $1,777 in 2022 and the firm projects that rates will rise another 7% to $1,895 this year. Indeed, auto insurance rates in Illinois actually remain 15.5% lower than the national average.

Inflation and continued supply-chain challenges are a big part of the story there. Increased rates of distracted driving also seem to be partly to blame. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, U.S. traffic fatalities reached a 16-year high in 2021, with 43,000 deaths.

But those are all trends in the underlying loss and claims data. Perhaps a transportation regulator could do something to reduce traffic accidents. The Federal Reserve does its best to stanch out-of-control inflation. But an insurance regulator can do neither. Since no insurer could stay in business particularly long charging rates that were unprofitable, the only way that rate regulation could actually reduce insurance rates is if a market were uncompetitive, allowing some writers to employ monopoly power to extract excess profits.

The evidence that this hypothetical describes Illinois is remarkably thin. There are 230 insurers that offer private passenger auto in Illinois. Based on the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), which the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Federal Trade Commission use to assess the degree of monopolistic concentration in a given market, the Illinois auto insurance market scored a 1,224 in 2021, the last year for which NAIC data is available. That falls short even of the FTC and DOJ’s threshold (1,500) for a “moderately concentrated” market. Auto insurance in Illinois is competitive.

Nor are the state’s largest auto insurers exactly swimming in profits. Allstate posted a $2.91 billion underwriting loss in 2022, driven primarily by results in the private passenger auto market. For GEICO, a subsidiary of Berkshire Hathaway, it was a full-year pre-tax underwriting loss of $1.88 billion. Bloomington-based State Farm, the largest auto insurer both in Illinois and in the United States, suffered a massive full-year underwriting loss of $13.2 billion.

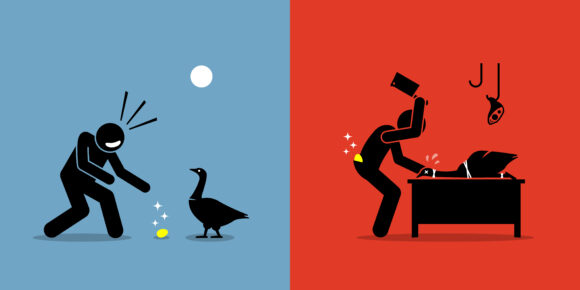

It would be one thing if adopting more stringent rate regulation simply failed to accomplish its stated goal of reducing rates, but the evidence is that it actually does manifest harm. The most obvious problem with rate regulation is that it restricts the availability of insurance. Insurers naturally respond to rate regulation by tightening their underwriting criteria, forcing some consumers to have to turn to the higher-priced residual market for coverage. In extreme cases, rate suppression can lead some insurers to exit the market altogether.

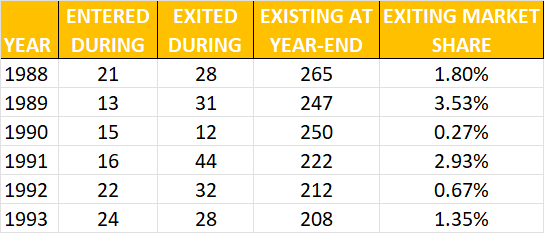

The empirical evidence of this effect is manifest. After California ordered mandatory 20% rate rollbacks following the passage of Prop 103 in 1988 (the effects of which were initially somewhat blunted by the courts), the number of insurers writing auto coverage in the state fell from 265 in 1988 to 208 in 1993.

FIRMS SELLING AUTO INSURANCE IN CALIFORNIA, 1988-1993

SOURCE: NAIC data

New Jersey, likewise, saw 20 insurers exit the market in the decade after the state passed the very similar Fair Automobile Insurance Reform Act. When New Jersey later liberalized its regulatory system with passage of the Auto Insurance Reform Act in June 2003, the number of auto writers more than doubled from 17 to 39 and thousands of previously uninsured drivers entered the system.

A similar effect was seen in South Carolina, where a restrictive rating system in the 1990s had forced 43% of drivers into residual market policies undergirded by a state-run reinsurance facility. After adopting a liberalized flex-band rating law in 1999, as in New Jersey, the number of insurers offering coverage in South Carolina doubled, the residual market shrank (it is, today, only 0.007% of the market), and overall rates actually fell.

Even in Massachusetts, which retains a fairly restrictive rate-approval process, reforms passed in April 2008 to allow insurers to submit competitive rates (they were previously set by the commissioner for all carriers) had a notable impact. Within two years of the reforms, rates had fallen by 12.7% and a dozen new carriers began offering coverage in the state.

Because it is still a very regulated state, Massachusetts still has a relatively large residual market. According to data from the Automobile Insurance Plan Service Office (AIPSO), in 2022, 3.38% of Massachusetts auto-insurance customers had to resort to the residual market, the second-highest rate in the nation. But before 2008, Massachusetts’ residual-market share was routinely in the double digits. The only state that still has double-digit residual-market share today is North Carolina, not coincidentally also the only state that still relies entirely on rates set by a rate bureau.

Lastly, regulation is not free. To finance the additional actuaries and financial inspectors needed to actually carry out this new regulatory system in Illinois, HB 2203 proposes that insurers subject to its provisions be assessed an additional fee of 0.05% of their total annual earned premium. Based on 2021 premiums, that’s an additional $14 million a year, which is in addition to the $106.4 million of fees and assessments the department already levies on the industry (not to mention the $515 million in premium taxes). The cost of these fees are, of course, passed on to consumers in the form of rate increases.

And what does that additional revenue actually get you? In 2021, Illinois spent $67.8 million on insurance regulation (which is, one should note, nearly $40 million less than it already collects in fees and assessments). California, by contrast, spent $245.5 million. Yet, California’s market is no more competitive than Illinois’, and arguably a lot less.

The Land of Lincoln should recognize that that’s a pretty bad deal.

Topics Illinois

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Political Violence in Polarized US at Its Worst Since 1970s

Political Violence in Polarized US at Its Worst Since 1970s  Average Cost of a Data Breach Has Reached an All-Time High: IBM Report

Average Cost of a Data Breach Has Reached an All-Time High: IBM Report  Zurich American Off the Hook on Harvard’s Legal Costs in Affirmative Action Case

Zurich American Off the Hook on Harvard’s Legal Costs in Affirmative Action Case  Liberty Mutual Posts Q2 Loss of $585M Driven By Catastrophes

Liberty Mutual Posts Q2 Loss of $585M Driven By Catastrophes