A relatively minor bureaucratic change proposed by the Federal Housing Finance Agency stirred up a viral storm in right-leaning news media recently, with outlets like the Washington Times, New York Post, National Review and Fox News all reporting some variant of the sentiment expressed in the Times headline: “Biden to hike payments for good-credit homebuyers to subsidize high-risk mortgages.”

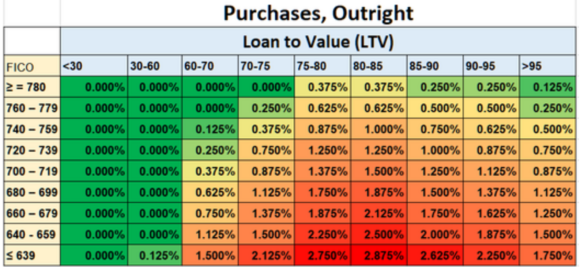

The underlying issue concerns the FHFA’s recent decision—as conservator of the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs)—to revise the loan-level price adjustments (LLPAs) charged by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which together account for roughly 60% of U.S. residential mortgage loans. The LLPAs that the GSEs charge are determined primarily by loan type, loan-to-value ratio and a borrower’s credit score.

What is broadly true in the coverage is that the changes—which were first announced in January, affect loans delivered to the GSEs on or after May 1 and therefore have already been implemented by lenders for months—do on balance tend to reduce costs for those with lower credit scores and increase costs for those with higher credit scores. In fact, as part of a broader repricing change announced last year, the FHFA eliminated fees altogether for conventional loans for about 20% of home buyers, financed by increased upfront fees for second homes, high-balance loans, and cash-out refinancings.

Unfortunately, the way this story has been spun in the wake of the changes would leave many news consumers with the impression that borrowers with higher credit scores will be paying more outright in fees than borrowers with lower credit scores. This is certainly not the case. Comparing apples to apples, at every level of the grid, a borrower with a higher credit score would continue to have lower LLPAs (or, in many LTV categories, none).

Writing in his Substack newsletter Kevin Erdmann of the Mercatus Center responded to a Fox News graphic that declared, under the new rules, a “620 FICO score gets a 1.75% fee discount” while a “740 FICO score pays a 1% fee”:

I’m pretty sure what they’ve done here is cherry pick the low credit score that had the largest fee decrease. Then, they reported the total fee of a higher credit score. So, a low down payment 620 score has a fee that went from about 6.75% to 5% (when mortgage insurance is included). And, also, the fee for a 740 score went from 0.25% to 1%. (plus a 0.25% mortgage insurance fee). Why didn’t they just say that fees for 740 scores went up 0.75%? It would still get their partisan point across. It would still be weird, because it would be describing mortgages with two different down payments. And it would hide the fact that the 620 score still has a fee that is more than 3% higher than the 740 score. But, at least it wouldn’t be mixing levels with changes.

Ultimately, whether these particular changes are good or bad for the GSEs is an actuarial question. As Erdmann goes on to note, there are good reasons to believe that the fees on lower-credit borrowers have been too high for an extended period.

But there are other reasons to be concerned about what the incident could mean for insurance markets. Here, the worry is that state regulators—or, in the worst-case scenario, Congress—might think charging those with high credit scores more to subsidize those with low credit scores might actually be an idea worthy of emulation.

Obviously, insurers’ use of credit information in underwriting and rate-setting has been a subject of public debate for going on four decades. At this point, while a handful of states prohibit the practice outright, most have adopted legislation that permits it, with some caveats.

The FHFA precedent—permitted because Fannie and Freddie have been in the agency’s conservatorship for close to 15 years—is particularly concerning given recent cases of state insurance regulators moving to limit or ban the use of credit information without any explicit direction from state legislators to do so. Whether courts choose to uphold such unilateral decisions depends on the particularities of state law.

Last year, Washington State Insurance Commissioner Mike Kreidler moved to adopt a permanent rule enacting a three-year ban on the use of credit-based insurance scores, after a predecessor emergency rule to do the same was declared invalid in September 2021 by Thurston County Superior Court Judge Indu Thomas. An August 2022 final order from Thomas found that Kreidler exceeded his authority in adopting the rule when there was a specific state statute that allowed insurers to use credit scoring.

More recently, the Nevada Supreme Court ruled in February to uphold a temporary ban on the use credit information in insurance rate-setting originally issued by the Nevada Division of Insurance in December 2020. The rule, which is scheduled to expire May 20, 2024, was unsuccessfully challenged by the National Association of Mutual Insurance Companies.

The rise of credit-based insurance scoring has revolutionized the industry, allowing vastly greater segmentation and better matching of risk to rate. Where state residual auto insurance entities once insured as much as half or more of all private-passenger auto risks, they now represent less than 1% of the market nationwide. It would be unfortunate if some misleading headlines inspired ill-considered regulation to reverse that progress.