Global financial firms, still smarting from multi-billion dollar losses in Russia, are now reassessing the risks of doing business in Greater China after an escalation of tensions over Taiwan.

Lenders including Societe Generale SA, JPMorgan Chase & Co., UBS Group AG have asked their staff to review contingency plans in the past few months to manage exposures, according to people familiar with the matter. Global insurers, meanwhile, are backing away from writing new policies to cover firms investing in China and Taiwan, and costs for political risk coverage have soared more than 60% since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“Political risk around potential U.S. sanctions and the likelihood that China would respond by restricting capital flow has kept risk managers busy,” said Mark Williams, a professor at Boston University. “A sanctions war would significantly increase the cost of doing business and push US banks to rethink their China strategy.”

Heated rhetoric between Beijing and Washington over Taiwan has unsettled firms, coming just months after Russia’s war unexpectedly forced the world’s largest lenders to exit businesses and stop serving ultra-wealthy clients. U.S. lawmakers last week ramped up pressure on banks to answer questions on whether they would withdraw from China if it invaded Taiwan.

While financial services executives who spoke on the condition of anonymity said they view the risk of armed conflict in North Asia as low, they see tit-for-tat sanctions between the US and China that disrupt the flow of finance and trade as ever more likely.

Any withdrawal would represent a dramatic about-face for Wall Street firms, which have poured billions into China after it opened its finance sector in recent years. Lenders ranging from Goldman Sachs Group Inc. to Morgan Stanley have taken control of joint ventures and sought more banking licenses, while adding staff until some recent cuts sparked by a drop deals. The combined disclosed exposure of the biggest Wall Street banks in banks in China was about $57 billion at the end of 2021.

Those ambitions are now threatened by rising U.S.-China tensions. Last week, Citigroup Inc. Chief Executive Officer Jane Fraser faced a grilling by lawmakers on whether the lender would pull back from China in the event of a Taiwan invasion. She answered in line with other banks — she would seek US government guidance before making a move.

“It’s a hypothetical question, but it’s highly likely that we would have a materially reduced presence if any at all in the country,” Fraser said.

Any pullback in China would only hurt these firms, China’s Global Times paper reported last week.

“American politicians want to pile on pressure to coerce top U.S. financial organizations to alienate the Chinese market,” the Communist Party paper said. “There is no denying China’s financial markets may lose some capital, but the U.S. banks may also face the worsening economic woes as a result of the poisonous decision from Washington.”

Over the past few months, firms have been stress-testing to see if they can handle the risk of a sudden market plunge — examining their exposure across the currency, bond and stock trading desks, people familiar said. While banks often draw up contingency plans without putting them into action, the escalating tensions are adding some urgency.

France’s SocGen has been assessing headcount in Greater China — including Hong Kong — driven by nervousness among executives in Paris, one person said. UBS has asked its Taiwan-based trading desk to assess its contingency plan and see how they can lower exposure to the island, according to a person familiar. One way would be to reduce foreign exchange trading services for Taiwanese clients, the person added.

Deutsche Bank AG has prepared as well and made plans that would enable it to move some regional assets and staff quickly in case of an emergency surrounding Taiwan, people familiar with the matter said.

Officials at all the banks declined to comment.

Trading Losses

Top of mind is ensuring staff safety, identifying clients who may be sanctioned, and looking at plans to mitigate counterparty risk and potential trading losses, according to two of the bank executives who asked not to be identified discussing a sensitive issue.

One banker said staff at their firm had considered the option of liquidating positions on China’s Financial Futures Exchange to cut onshore counterparty risk, replicating those contracts on other exchanges such as in Singapore.

Meanwhile, insurers have raised prices by 67% on average for political risk coverage linked to China, according to Willis Towers Watson Plc. Businesses that can get insurance face a “steep reallocation” of pricing, which has been “very acute” for China, according to Laura Burns, senior vice president for political risk at London-based Willis Towers Watson.

Insurers are underwriting new policies, but “cautiously and selectively” in China and have reduced their capacity for Taiwan exposure, said Nick Robson, head of credit specialties at broker Marsh & McLennan Cos. Political risk insurance pays out if a client loses money due to political events such as civil unrest, terrorism or war.

HSBC Challenge

At HSBC Holdings Plc, the global lender most heavily exposed to China and Hong Kong, calls by its biggest shareholder to carve out the Asian business have been driven partly by concern it’s susceptible to a decoupling between the US and China.

Ping An Insurance Group Co. would back a breakup of HSBC’s Asia business or just the Asia retail operations, a person familiar has said. The lender, which was founded in Hong Kong and Shanghai in 1865, has been increasingly looking to invest in other markets such as India to cushion any financial impact from volatility in some parts of North Asia, a person familiar has said. CEO Noel Quinn has resisted calls for a breakup. The bank declined to comment.

Planning for the spectrum of scenarios is no easy task, especially with executives wary of alienating Chinese officials on an issue of extreme sensitivity. One senior private banker in Hong Kong, who works with wealthy Chinese clients at a European bank, says the topic is so taboo that bankers are reluctant to hold formal discussions or put plans in writing for fear of it getting back to Beijing.

“Some of the banks who are the most exposed are the most fearful to plan long term, for fear of backlash from China,” said Isaac Stone Fish, founder of Strategy Risks, which specializes in corporate relationships with China. “Banks having a lot of these conversations are doing it outside of China and Hong Kong.”

Russia Lessons

In some cases, executives worry about a situation — much like in Russia — where Beijing blocks foreign banks from moving assets or capital abroad as a payback for any U.S. sanctions.

Russian authorities plan to review individual requests on the sale of foreign bank units in the country without instigating a blanket ban on such deals, two officials familiar with discussions on the matter have said earlier. The government will consider every application and decide to grant permission if it’s deemed beneficial for the nation, the officials said.

The Interfax news service had earlier cited Deputy Finance Minister Aleksey Moiseev as saying that a government subcommittee on foreign investments would reject all sales requests from foreign banks to sell their units “until the situation has improved.”

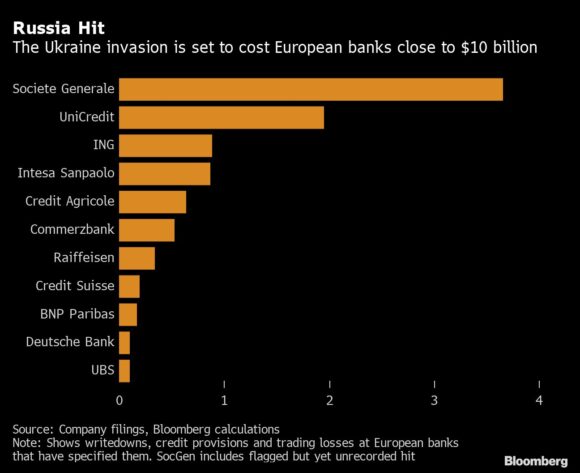

European banks including Societe Generale and UniCredit SpA have flagged combined hits of almost $10 billion from Russia, mostly from writing down the value of their operations and setting aside money as a shield against the expected economic ramifications.

“Russia has proven to be a template of what you don’t want to happen,” said Dale Buckner, CEO of security services firm Global Guardian, whose clients include banks and private equity firms. “People are asking the ‘what if’ questions: if there was a blockade, if there was shut down of the cyber system, if there were naval strikes or an actual war. What would happen?”

The first part of the calculus would be to review hard assets and intellectual property in the region, understand where a firm’s money is parked and who has control if China decided to take over the banking system and deny access, he said.

“It’s almost impossible to plan for these things,” said Tom Kirchmaier, professor at the Centre of Economic Performance at the London School of Economics. “While there has been some planning for these scenarios since the financial crisis, there no doubt will be some big surprises when theory hits practice.”

–With assistance from Harry Wilson, Cindy Wang and Steven Arons.

Topics China

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Heritage Insurance Reports Third Straight Quarter of Profit After Shedding Policies

Heritage Insurance Reports Third Straight Quarter of Profit After Shedding Policies  Inflation, Catastrophe Losses Lead P&C Underwriting Loss in 2023

Inflation, Catastrophe Losses Lead P&C Underwriting Loss in 2023  ChatGPT Fever Spreads to US Workplace, Sounding Alarm for Some

ChatGPT Fever Spreads to US Workplace, Sounding Alarm for Some  Commercial Property Loans Are So Unappealing Banks Trying to Dump Them

Commercial Property Loans Are So Unappealing Banks Trying to Dump Them